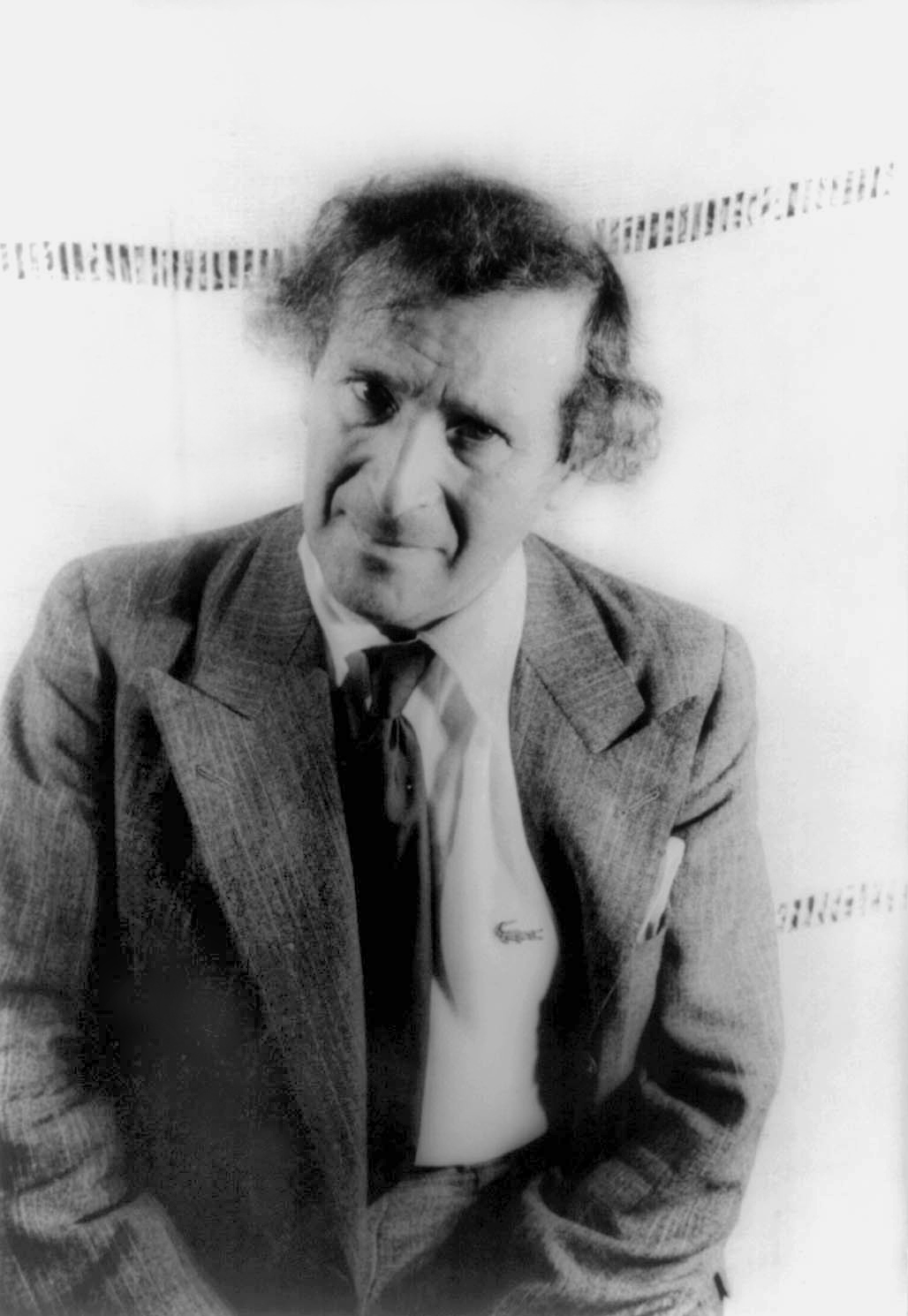

I cannot claim to be a Woody Allen connoisseur. I humbly confess that I have seen only Manhattan and Annie Hall, which would send many an Allenite to haughtily dismiss anything I say. But I refuse to believe that one absolutely must be fully acquainted with the full oeuvre of the artist in order to critique it. Some movies simply do not work, and you need no encyclopedic knowledge to see it. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Vicky Cristina Barcelona is of this very breed.

Our story begins with two polar opposites: Cristina (Scarlett Johansson), impulsive and idealistic, and Vicky (Rebecca Hall), rational and clear-headed. One blonde, one brunette; one flirtatious, one standoffish. From the first two minutes of the film, problems arise. The familiar Cartesian division of reason and emotion is simply too stereotypical; no women-- or men, for that matter-- are so distinctly cookie-cutter. These first few minutes that we see of Vicky and Cristina, sitting in the taxi in Barcelona, already become problematic. And not only is it odd from a feminist perspective-- it's also completely uninteresting, and entirely overdone. We have seen this again, and again, and again, and again since the Golden Age of Hollywood. Must we see it once again in 2008, a pre-Freudian, pre-Jungian complete misunderstanding of the human psyche?

Woody Allen, we understand that you do not understand women. But to assume knowledge when you create your female characters is already out of your line. Where is the complexity of Annie Hall? There is even an amount of condescension falling on Vicky and Cristina, as if they were just young and silly and didn't know any better.

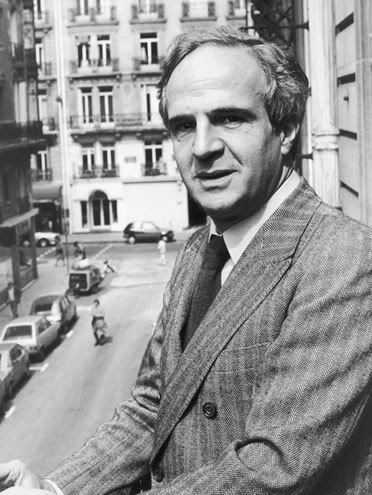

Vicky and Cristina are joined by even more stereotypical characters later on, as they are taken in by an American expatriate haute-bourgeois middle-aged couple, and meet the "sexy" "bohemian artist" Juan Antonio at an art auction. Cliches run wild, and soon we see the breathtaking Maria-Elena (Penelope Cruz), the completely insane ex-wife of Juan Antonio. Cristina is whisked into the confusing and somewhat dystopian love triangle between the two ex-lovers, and is enamored by the "bohemian" lifestyle. What this movie makes clear, more than anything, is how little Woody Allen understands of this so-called "bohemian" artistic lifestyle. There is nothing original in his portrayal of what could have possibly become full-rounded characters; they are like Platonic Forms rather than characters, Maria-Elena as the Form of the Mad Genius, Cristina as the Confused Idealizer, Vicky as the Rational Soul Hiding a Wilder Heart. 8th-graders could have created a more interesting plot.

Which is not to say, however, that I left the movie disgusted. Confused, full of criticism, but somehow satisfied. Though the ending was more than unsatisfactory-- a sort of disheartened deus ex machina of the "it was all a wonderful dream" variety-- it was still, well, set in Barcelona. And Barcelona is beautiful. And, of course, those subtle things that make the movie so characteristically Woody Allen-esque (lunettes, overwhelming amounts of unnecessary voiceover, simple beginning and ending credits...) The only quotable part of the movie was Juan Gonzalez near the end of the movie: "We work, and we do not work at all. We are a contradiction, and some would say that is love," or something of that sort. Perhaps an interesting concept amidst a not-so-interesting film.